As the principal investigator in the phase III trials of the Rotovac vaccine to prevent rotavirus related gastroenteritis Gagandeep Kang is “very excited” with the publication of the results of a study that established the effectiveness of the vaccine, country wide.

Currently director of the global health team at the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation, responsible for enterics, diagnostics, epidemiology and genomics portfolio, Dr. Kang, in a previous position with the Christian Medical College, Vellore, built extensive surveillance networks to study enteric infections, the category in which rotavirus falls. This body of work provided crucial insights into the epidemiology of the disease and helped create and clinically test Rotovac, a vaccine developed by the Department of Biotechnology, Bharat Biotech, the U.S. National Institutes of Health, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Stanford University, and PATH, with support from the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.

Trials vs community impact

“When we do vaccine trials, the question always is whether the impact will be similar as the results of our trial when it is deployed in the community,” she pitches in pragmatically, on a call from Seattle. Dr. Kang goes on to explain: “After all, as part of the trial, we usually recruit healthy people; they have a set regimen to receive the doses, and we can follow them up regularly, in order to make sure that the best possible outcomes are achieved. Will it work in the real world, where children are malnourished, there is a possibility that they may not get all the three doses, and the conditions of trial are vastly different from the situation they are in? Does the coverage have to be complete for it to have effect?”

“This study is a test-negative trial that comes when the government has begun delivering the vaccine to children for years now. What researchers are doing basically is waiting in hospital, looking to see how many children who come in for treatment for diarrhoea have received the vaccine. If more children in hospitals with diarrhoea have not been vaccinated, it proves that the vaccine is working.”

In this study, the result was that the effectiveness was about 54%, which is what emerged during the efficacy trial too. She points out that while the trial had 200 participants, this study looked at over 4,000 children.

“A successful trial is wonderful, but how we perform outside of trial circumstances is key. However, questions remain – are there places where it works better; what about coverage?” Dr. Kang adds. “Every vaccine intends to be 100% but the truth is no vaccine is 100%. We have to look for ways to improve protection,” she explains.

It may be recalled that there were concerns that Rotovac was causing intussusception among children – a condition wherein a part of the intestine slides into an adjacent section, causing a blockage in the digestive tract. “However, we did a safety study and there was zero evidence of this. Subsequent data also clarified that intussusception was not a side effect of administering Rotovac,” Dr. Kang says.

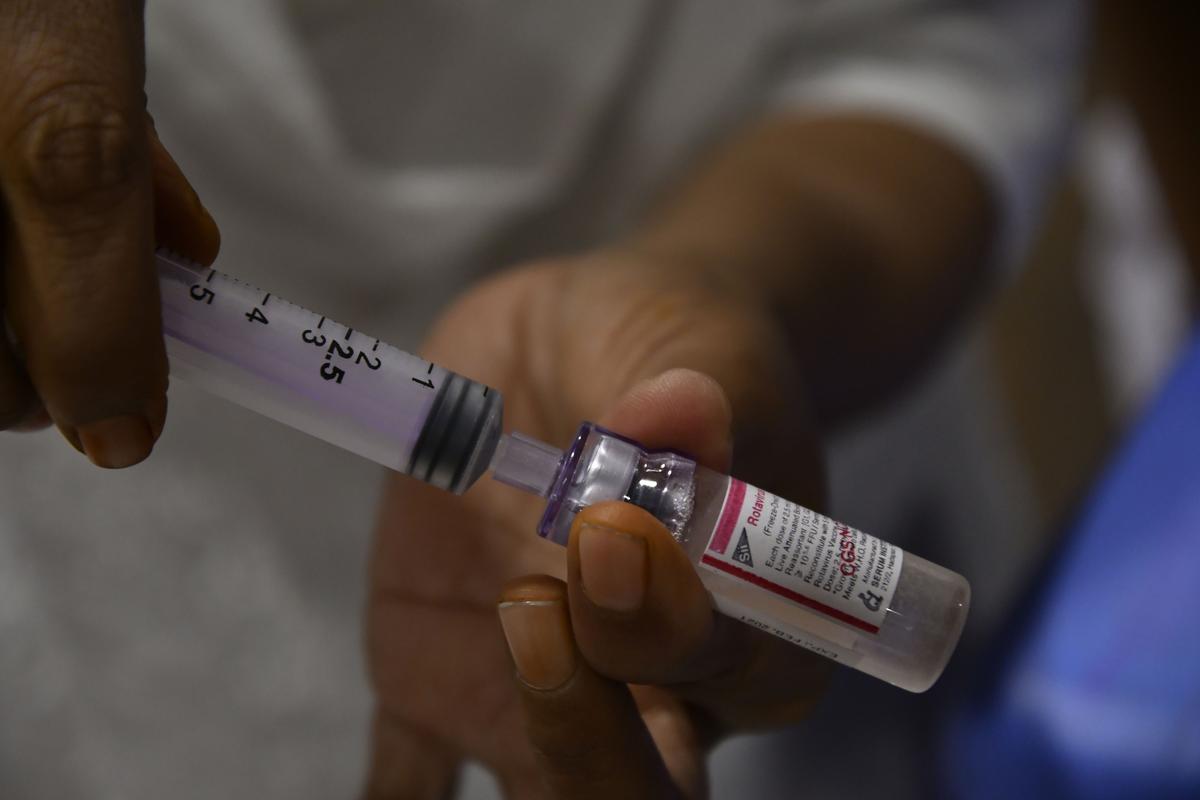

The game changer was the introduction of Rotovac into the Universal Immunisation Programme, says Dr. Kang. File photograph

As good as global vaccine

What does this mean for India, particularly at a time when questions are being raised about pharma standards in the country? “What it tells us is that Rotovac is as good as any other international vaccine. Our companies are making really good vaccines. India is also doing well in terms of vaccinating against rotavirus, which was introduced in some States in 2016. By the end of 2019, it [was] being offered all over the country, free,” she says. “Initially there were glitches, but the government is doing a remarkable job now. About 90 % of the target population is being vaccinated and given our huge birth cohort, that is indeed a remarkable thing. But this still means about 10% of the population is not getting the vaccine and we need to reach them also,” Dr. Kang explains.

A tool for equity

The game changer she insists was the introduction of Rotovac into the Universal Immunisation Programme. “If you look at the private health sector in India, children are getting access to any vaccine that any other child in other parts of the world has access to. But we need to think of equity and every child has a right to be protected – that is something only the UIP can do. In 1986, measles was included in the UIP, but after that, for more than 20 years, there were no additions until the Pentavalent vaccine. Since then, we have introduced Rotavirus, and pneumococcal vaccine, besides the injectable polio. The National Technical Advisory Group on Immunsation has approved the HPV and typhoid vaccines, and it would be great to see them included in to the UIP – which is a tool for equity,” Dr. Kang explains.

At a time of .free-ranging vaccine skepticism, she exhorts all people who believe in evidence and rationality to work together. “Those who are not informed are happy to believe in conspiracy theories,” she says, “We have to built trust in science – which places caveats. It is important to declare and be open about what we know and we don’t know. This is not a negative; it is a fact, and it allows us to [be] open to what evidence will subsequently reveal.”

Promote critical thinking

The naysayers, however, are confident in their ignorance and do not care about the truth. The way to beat this. Dr. Kang says, is to have a scientific temper, promote critical thinking and train ourselves to look for good, reliable sources of information, versus picking up attention-grabbing tidbits. “But it is difficult, I’ll admit. There is a firehose of disinformation out there now.”

Published – October 18, 2025 09:37 pm IST