If there were a chemical formula for happiness, dopamine would be at its core. Often called the “feel-good” neurotransmitter, dopamine drives motivation, reward, and pleasure, whether from a good meal, an achievement, or a meaningful relationship. From drug addictions to social media marathons, contemporary life has made dopamine a double-edged sword that both stimulates productivity and feeds addiction.

The brain’s reward circuit

Dopamine is a chemical signal that conveys pleasure and thus a sense of reward. Each time something happens that makes us happy, such as eating chocolate or receiving a compliment, our brain releases dopamine, prompting us to act in the same manner again. On a neurobiological level, this is largely contingent on the mesolimbic pathway from the ventral tegmental area (VTA) to the nucleus accumbens, a central part of the brain’s reward pathways. The mesolimbic pathway reinforces behaviours we perceive as constructive or pleasurable, along with reward prediction and a motivation to learn.

Certain times, these processes are commandeered by addictive drugs including cocaine, nicotine, or alcohol. Such drugs induce massive dopamine surges, overwhelming the reward centre of the brain. Over time however, the brain gets desensitised, requiring more doses of the addictive substance in order to feel normal. This is where addiction begins — not from pleasure itself, but from the brain trying to bring balance back.

From substances to screens

Drugs used to be the primary cause of dopamine overload, but now, technology is the new push. Every ping, like, and notification serves to deliver tiny doses of dopamine, delivered intermittently, to promote user engagement in a reward schedule that best resembles a slot machine. Social media, short videos, reels, and streaming services exploit this gap, producing dependency with their endless cycle of suspense and satisfaction.

Although scrolling on Instagram or watching endless short videos may feel harmless, neuroscientists have shown that the brain processes the kind of stimulation presented by technology similarly to actual drug use. Such use promotes compulsive checking behaviours, fractured attention, anxiety, or withdrawal when disconnected. Functional MRI studies have shown overlapping activation in the nucleus accumbens during social media engagement and substance use, supporting the idea that digital stimuli can trigger the same reward circuits that drive addiction.

What is more concerning is that dopamine-driven design is not coincidental — it is a result of behavioural engineering, in which algorithms find out what rewards you the most and serve you more of it.

Progression over time

Previously, dopamine was associated with real-life experiences — achievements, relationships, and learning. However, with technological advancements, pleasure has become instant and plentiful. Television and video games in the 1990s provided minimal stimulation; smartphones nowadays provide an unlimited supply of customised content. The human brain has not, however, developed quickly enough to manage this deluge of stimuli. What took effort and patience in the past is now substituted with instant gratification — one click, one swipe, one scroll.

What does excessive screen time do to your brain? | In Focus podcast

Young adults and teenagers, who are still learning how to manage their emotions and impulses, are especially susceptible. Research indicates that adolescents who report spending more than three hours a day on social media report substantially higher levels of anxiety and depressive symptoms. The adolescent brain is particularly plastic in development. This means that under-stimulation from the world around them and overstimulation from technology may, quickly yet casually, shape their reward circuits — creating hyper-short attention spans and emotional instability. Excessive screen time is shown by research to change the sensitivity of dopamine receptors, making it more difficult to find pleasure in daily life. Short of that, our normal baseline happiness is decreasing, while our appetites for stimulation become stronger.

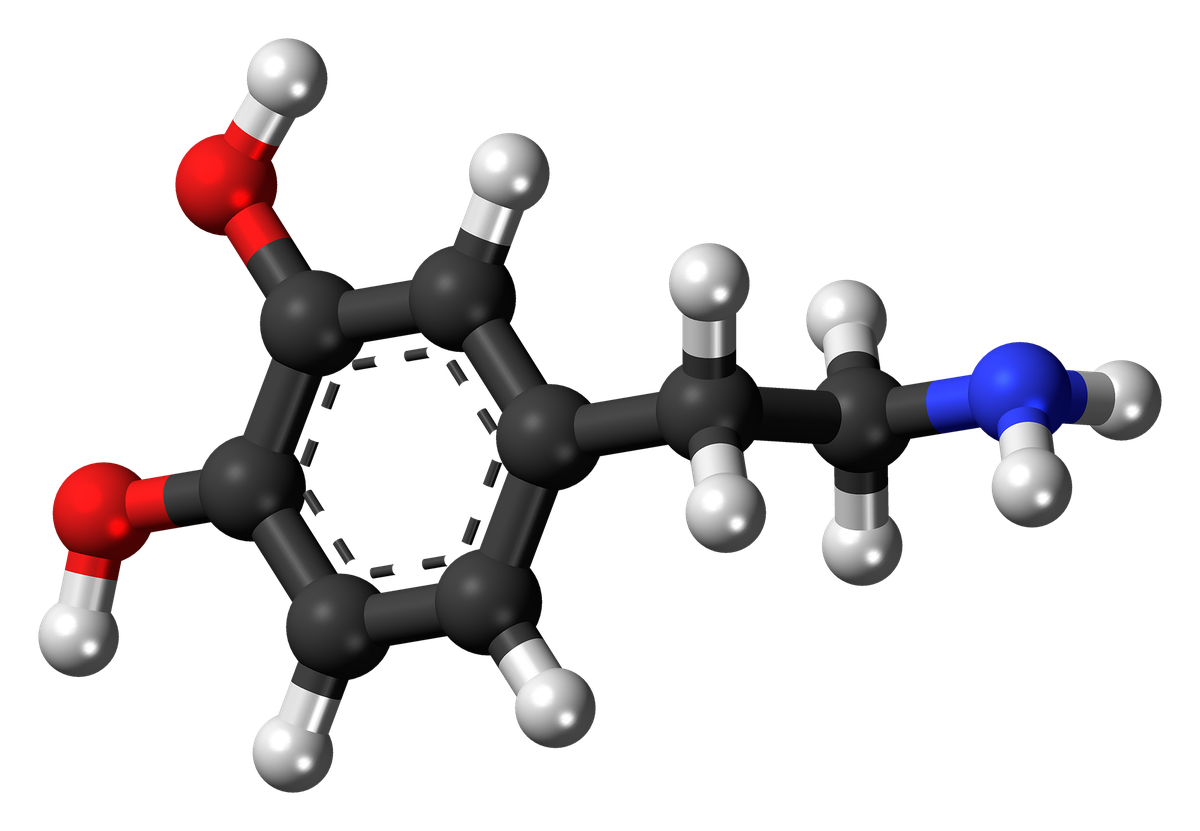

A ball-and-stick model of the dopamine molecule

| Photo Credit:

Jynto, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Dopamine overload

An overload of dopamine does not indicate that we are off the charts happy; it suggests that our brain’s reward system may be fatigued. By constantly seeking out stimulation, we are unknowingly setting ourselves up for burnout. The implications may be slow and stealthy at first: the experience of losing motivation when performing a normal task as it feels bland compared to an immediate sense of stability experienced while waiting for digital affirmation or enjoying the pharmacologic effects of a substance. Eventually, wear and tear will dull our emotional responses to regular experiences, for instance, the ability to experience, joy, and will interrupt sleep, shorten our attention span and begin to deteriorate our mental health with anxiety, depression and poor self-esteem.

It is possible to use social media engagement to stimulate reward circuits in the brain that resemble what drives some to addiction. When the brain becomes accustomed to constant spikes of pleasure and begins screaming for more, potential manifestations include addiction, whether social media, video games, or drugs.

Reclaiming balance

The solution, of course, is not to eliminate dopamine, but rather to bring it back in balance. “Dopamine fasting” refers to taking a break from the defeating pleasure and excitement our brains tend to rely on and instead, attempting to retrain our brains to function appropriately with a more moderate and sustainable level of happiness when engaging in slower and deeper experiences. Taking time away from constant phone reminders, silencing emails, taking a break from your devices, making your devices grayscale, or simply instituting a tech break can help your mind reset its rhythm.

Regular movement and moderate engagement with mindfulness will allow you to experience dopamine naturally and at a more stable and healthy level, instead of the non-stop hyper-stimulating level we are used to in the present. Focusing on meaningful activities — deep work, learning new skills — also ushers in enjoyable experiences with slower, more lasting rewards.

The most important return to balance comes with real human connection — a good old-fashioned conversation, a laugh with a friend, or time spent with family that provides a level of happiness that no social media ‘likes’ can match. Ensuring good sleep, good nutrition, and emotional awareness helps stabilise dopamine levels and grounds our moods.

Risks and resets

The epidemic of dopamine does not discriminate, and yet, it is Gen Z and younger millennials who are bearing the burden. The brains of these two generations are wired for rapid and frequent stimulation, and as a result, they are prone to emotional depletion.

The first step towards changing this is awareness. Knowing the role of dopamine and how it functions gives us control, so that we are not controlled by it. The intent is not to escape pleasure, but to find balance between excitement and tranquillity, stimulation and calmness.

From a psychiatric perspective, prevention begins with awareness and structured routines. Promoting consistent sleep hygiene, mindful technology consumption, physical activity, and authentic social connections are just a few of many methods used to increase mental resilience. As modelling of balanced behaviours lies within the purview of parents, teachers, and clinicians, they can help the next generation modulate their experience with pleasure and motivation in the process of building healthy relationships.

In an environment that rewards immediacy, the greatest pleasure is to slow down — to earn that high by choosing focus over frenzy, presence over pings, and purpose over pleasure. Because true pleasure, as it turns out, isn’t about chasing dopamine – it is about harnessing it.

(Dr. Pretty Duggar Gupta is consultant psychiatrist, Aster Hospital, Bengaluru. [email protected])