One must never underestimate the power of technology in impacting society. Today, the revolution of AI has been making our lives easier, but over centuries ago, one machine not only came to be a technological breakthrough, but also geared society to where it is today — democratised education, individual thinking, and communication on a mass level — that machine was the printing press Today, we will explore the impact of the printing press on society and its thinking.

Life before the press

Printing to progress

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Early methods of printing were seen across different communities and countries. The earliest form dates back to the 4th millennium B.C., where cylinder seals were used to certify documents on clay tablets. Pottery imprints, cloth printing, and coinage were also early forms of printing. Woodblock printing was done on silk and paper. Originating in China in the 7th Century A.D., the method subsequently spread to other parts of Asia and even to Europe.

The turning point

Johannes Gutenberg

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

Woodblock printing was also popular in Europe until the 15th Century, when the late medieval German inventor Johannes Gutenberg created the first printing press based on previously known presses and techniques. By the end of the 15th Century, the Bible was printed on a very large scale, and even today it is the world’s best-selling and most printed book, with over five to seven million copies printed and sold.

With the help of Gutenberg’s printing press, printing could happen on a large scale and at a low price. This helped democratise access to books, education, and ideas for common people and elites alike.

Subsequently, the printing industry spread throughout Renaissance Europe, and eventually among publishers and printers that emerged in the British American colonies. What then followed was a sharing of ideas on a large scale, leading to the printing press spreading globally.

Print revolutionised communication on such a level that revolutions amplified to a big time extent. Let’s look at it in detail.

Renaissance

Printing towards progress: How the printing press changed society

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Italian Renaissance began a century before the printing press was invented, when political leaders in Rome and Florence sought to revive the traditional Ancient Roman education system. Their objective was to revive texts of figures like Plato and Aristotle and have them republished. Rare texts were translated into Latin by Italian emissaries (diplomats) who knew enough Arabic and Ancient Greek. The process started long before the printing press, but it was so slow and expensive that only the richest of the rich could afford it. Print didn’t quite launch the Renaissance, only accelerated it.

Scientific Revolution

English philosopher Francis Bacon is credited with the development of the scientific method. In 1620, he considered the printing press one among three inventions that changed the world, the other two being gunpowder and the nautical compass.

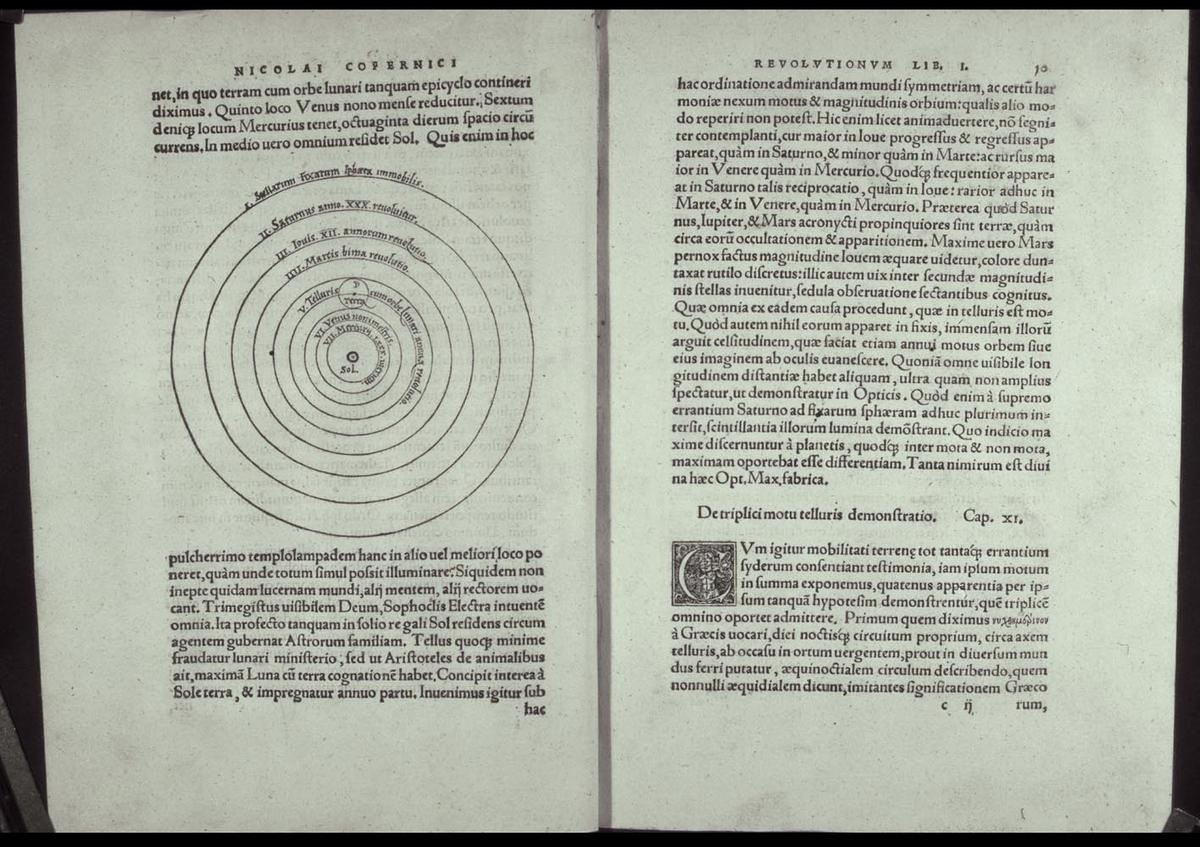

Science has been a pursuit for humankind for millenia. Mathematicians across the world were separated by geographical and lingual boundaries, and sloth-like handwritten publishing. Their works were not only expensive, but also prone to human error. With the print revolution and a newfound ability to publish and share ideas on a large scale, science took a big leap in the 16th and 17th Centuries.

The press not only offered faster printing, but also accuracy in its data, which proved to be very helpful for scientists.

To add to that, when Gutenberg switched to metal type in 1450, there was more precision guaranteed. Maps of the world and the sky, and anatomical diagrams could be made with extra precision. It was so precise that astronomer Nicolas Copernicus could create his model of the galaxy with the help of astronomical tables aiding his own observations.

Rebelling against the Church

Martin Luther

| Photo Credit:

WIKIMEDIA COMMONS

The Church played a powerful role in shaping religion, culture, politics, and daily life. But all that crumbled slowly, thanks to Gutenberg, and a few other figures who tried to raise their voices against the Church.

You may have heard the story of Galileo Galilei shutting the Church down with this take on heliocentrism, i.e., the idea that the Earth revolves around the Sun. But here’s a man who took his ideas to another level.

Martin Luther was a scholar and theologian who cleverly summed up the role of print in Protestant Reformation, quote: “Printing is the ultimate gift of God and the greatest one.”

His work, 95 Theses, centred around two beliefs — that the Bible is the central religious authority and that humans may reach salvation only by their faith and not by their deeds. This in turn started the Protestant Revolution, thereby dividing the Catholic Church, and changing the course of history for religion.

With new technology come new voices, and print gave a platform to those who were silenced. In the context of the print revolution, this included egalitarian groups, and critics of the government. And as the public got stronger and more opinionated, those in power came back stronger with censorship, which was relatively easy before. But with the emergence of print, nothing could stop the public. Every time the Church made a list of banned books, booksellers hit back by getting these books printed.

To each their own and out there

During the Enlightenment era, works of philosophers like Jean Jacques Rousseau, and Voltaire, were popular. Their emphasis on reason over tradition made people question religious authority and value personal liberty. This led to the development of public opinion, and their courage to challenge and even overthrow elites. French writer and dramatist Louis-Sébastien Mercier declared print to be “the most beautiful gift from heaven,” believing it would soon “change the countenance of the universe” and make “tyrants of all kinds… tremble before the universal cry that echoes everywhere”. And he wasn’t wrong.

Taking to India

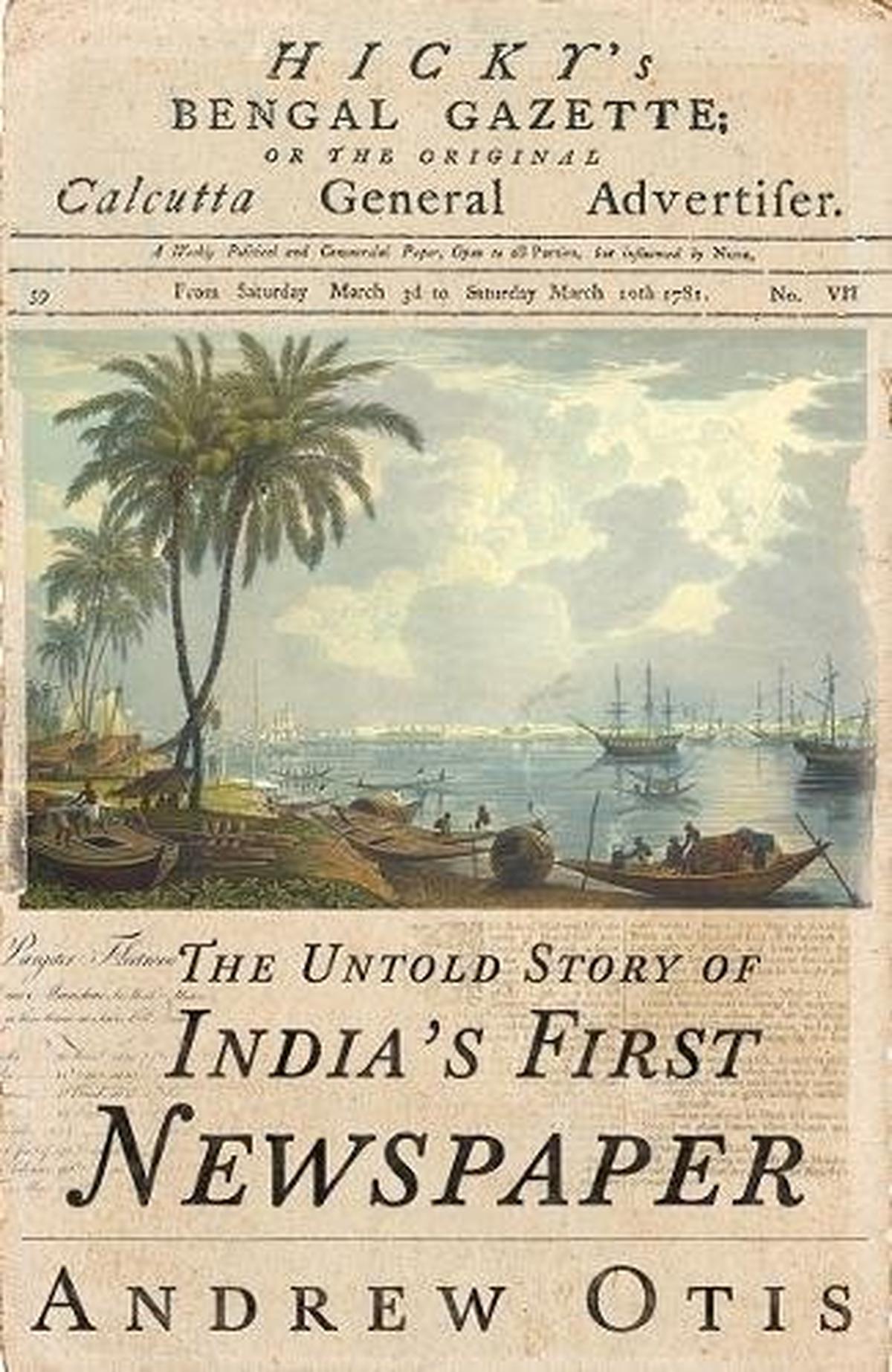

The Bengal Gazette

| Photo Credit:

SPECIAL ARRANGEMENT

Print in India dates back to the 16th Century when the Portuguese introduced it to Goa. Subsequently, the first printing press was set up in 1556, at St. Paul’s College, Goa. It was primarily used for printing religious material for Christians in India.

In 1579, Jesuit Thomas Stephens came to India seeking to spread and develop the Konkani language. He also wrote Krista Purana (transl. “Life of Christ”) in the Marathi language, which was based on Ramayana. That same year, the first Tamil book was printed by the Catholic priests.

Over time, more printing presses were established across India which spurred the development and spread of literature in various Indian languages. The launch of India’s first newspaper, the Bengal Gazette in 1780, by James Augustus Hickey, made print a hub for new ideas and public discourse.

Much like in Europe, there was an impact on religion and culture, an increase in literacy rates and the growth of more forms of publication.

There were also attempts of censorship with enactments like the Vernacular Press Act of 1878, which curtailed the freedom of the Indian press and prevented the expression of criticism toward British policies. Nevertheless, that did not stop them and print significantly fuelled the country’s independence movement.

The press did more than just replicate books — it replicated knowledge, fuelled revolutions and unlocked minds. It laid the foundation for what society is today. Today, as we scroll through texts and share ideas with a click, it’s worth remembering that this modern literacy journey began with one invention and the vision of a man who believed that education should belong to everyone.