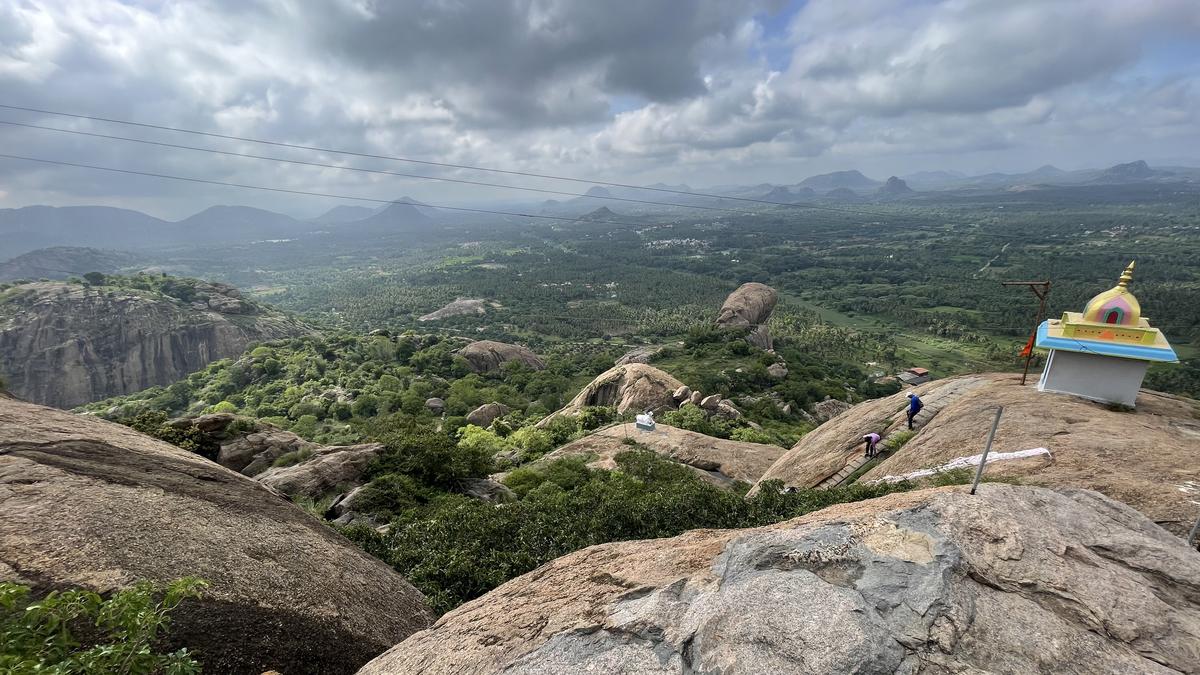

Stretching across much of peninsular India, the Deccan Plateau hides a silent, subterranean struggle. Beneath its sunbaked soil lie ancient, fractured layers of basalt and granite — hard rock aquifers that dominate the region’s groundwater story.

In Karnataka, this rocky reality is nearly absolute: about 99% of the State relies on these stubbornly unyielding formations for its water needs. With limited porosity and a dependence on narrow fractures and weathered pockets to store and move water, these geological formations offer far less than they promise, unlike the generous flow of sedimentary aquifers.

In a new study, researchers from the Water, Environment, Land and Livelihoods (WELL) Labs in Chennai examined Aralumallige and Doddathumakuru gram panchayats in the Upper Arkavathy watershed near Bengaluru, revealing a sharp decline in groundwater levels driven by intensive agricultural practices.

These areas supply vegetables, exotic crops, and flowers to Bengaluru, banking on water-intensive farming. While monsoon rains offer seasonal relief, farmers depend on deep borewells for the rest of the year. Borewells drilled into granite bedrock alter the subsurface geology, creating microfractures that fasttrack rainwater deep underground. As a result, instead of recharging shallow aquifers, water bypasses them entirely, disrupting the local hydrology and weakening long-term water retention.

Every year, the water table continues to drop. According to the study, published recently in PLoS Water, the average depth of gram panchayat drinking water borewells dramatically increased from 183 m during 2001-2011 to 321 m in 2011-2021. Thus almost 55% of all wells drilled in the Aralumallige sub-watershed have failed, with a staggering 70% of drinking water wells failing within a decade of their construction, primarily due to falling water tables.

The study also highlighted water quality issues. While nitrate levels in drinking water were often higher than the prescribed norm of 50 mg/l, people didn’t abandon their wells. Interviews with gram panchayat officials revealed that only two of the 79 abandoned borewells were shut due to elevated fluoride concentrations.

The findings collectively suggest groundwater quality issues, while acknowledged, aren’t the primary drivers of borewell abandonment. Instead, the overwhelming cause is the chronic and severe depletion of the water table.

Mounting challenges

Electricity is free for farmers, but gram panchayats are grappling with a mounting economic crisis. The frequent drilling of deep borewells, which require powerful pumps, has pushed them into steep electrical debt. Revenue collection can’t cover the ballooning annual power bills, directly affecting the ability of panchayats to maintain rural water infrastructure. Funds meant for development projects are being redirected to cover utility costs, stalling local progress. Meanwhile, the State government has begun pressuring panchayats to pay outstanding taxes despite their financial strain.

Borewell drilling costs are borne by individuals. For small farmers, this means investing ₹4-5 lakh in a single borewell, with no guarantee of success. Many end up leasing their land and migrating to urban areas for a stable income. Labour, pump installation, and infrastructure expenses have hit the rural economy hard.

Despite widespread awareness of water scarcity, there have been few efforts to educate farmers on the consequences of water-intensive cropping. The region’s terrain limits greywater reuse and youth migrating away further disrupts sustainable practices.

While Karnataka banned eucalyptus farming due to the species’ high-water use, its long-term impact on groundwater persists.

The new study also pointed to a broader concern: despite widespread groundwater overexploitation, there is very little quantitative evidence on the risks to water sustainability at the local level. This makes it difficult to predict borewell failures or estimate the true costs faced by drinking water authorities.

The researchers have argued that poor water resource management is the biggest threat to sustained rural drinking water access in India. While global ‘water, sanitation, and hygiene’ initiatives focus on technical and financial infrastructure, they often overlook the foundational problem: neglected resource management.

Efforts in motion

In the study, the researchers used data from the Sujala Project, a key groundwater recharge initiative by the Karnataka government, to trace depletion trends. They also referenced the Jal Jeevan Mission, India’s flagship programme for universal piped water access, which has funded new infrastructure and replaced failed borewells. While the study wasn’t directly critical of these programmes, it argued that long-term success hinges on addressing the root crisis: groundwater depletion and the financial strain it imposes on local governance.

As Lakshmikantha N.R., one of the study’s authors, put it: “Until and unless you change the farming technique of over-extraction, no amount of recharging will change the state of the groundwater” in Aralumallige, Doddathumakuru, and other rural parts of the Deccan Plateau. He also recommended that gram panchayats begin compensating farmers for using less electricity and extracting less water, encouraging more sustainable practices while reducing rising electricity bills.

“If such an initiative isn’t taken,” he warned, “within 3-4 years there will be no groundwater left to drink or use.”

Until the 1970s, Bengaluru depended on tanks and reservoirs to replenish groundwater. But with the advent of borewells, which operate on shorter timescales, traditional systems were abandoned. In Aralumallige, the local lake, once a key recharge reservoir, has now been encroached upon, its soil dug up, its green cover denuded. Before borewells, the lake’s discharge channels helped recharge surrounding areas. In 2022, despite heavy rainfall, the lake remained dry.

The findings paint a sobering picture: without urgent shifts in agricultural practices and stronger local governance, groundwater in the Deccan Plateau may slip beyond recovery. According to the researchers, sustainable farming, recharge infrastructure, and policy incentives must work in tandem and not as afterthoughts. The study recommends better policies and technologies to help rural farmers and governing bodies use their resources without inviting a crisis.

Neelanjana Rai is a freelance journalist who writes about indigenous community, environment, science and health.

Published – July 02, 2025 05:30 am IST