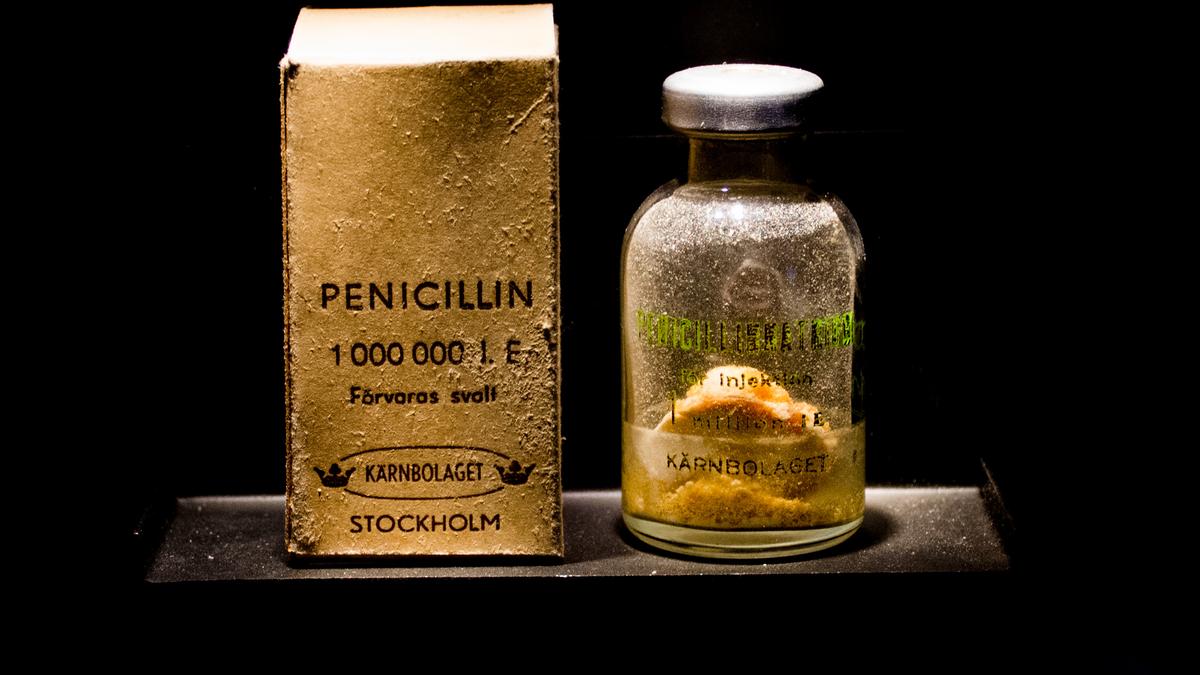

There are some inventions and discoveries that have an instant impact, changing our ways immediately and having a marked effect quickly. There are others that take time to make their presence felt so as to say, time during which we humans figure out the actual usefulness and put it to action in a better way. The story of penicillin nicely fits into the second class as we needed more than a decade to figure out that it was a magic drug.

Penicillin’s discovery

The story of penicillin begins in 1928 with Alexander Fleming, a doctor and researcher at St. Mary’s Hospital Medical School in London. In September that year, when returning to his basement laboratory following a holiday, he began sorting through petri dishes containing colonies of bacteria that cause boils and sore throats.

Amidst this he noticed something strange. He saw that one dish was dotted with colonies of bacteria, barring one area where a stray mould was growing. The region around the mould was clear – an indication that the bacteria had been killed.

Recognising the significance of his observation, Fleming tried to identify the antibacterial substance responsible for this, calling it penicillin. He published his findings in the British Journal of Experimental Pathology in June 1929, but it only carried a passing remark at best about penicillin’s therapeutic benefit. Fleming and his team were neither able to isolate pure penicillin, nor realise its full potential, leaving it for others to further develop.

Howard Florey, ahead of a lecture on penicillin.

| Photo Credit:

Wellcome Library, London / Wikimedia Commons

Florey’s team at Oxford

The bulk of that development came from a team in Oxford headed by Australian pharmacologist and pathologist Howard Florey. When Florey came to Oxford in 1935, he was the newly appointed Professor of Pathology in the new Sir William Dunn School. He quickly set about putting in place a research team and in a short time had recruited German chemist Ernst Chain from Cambridge.

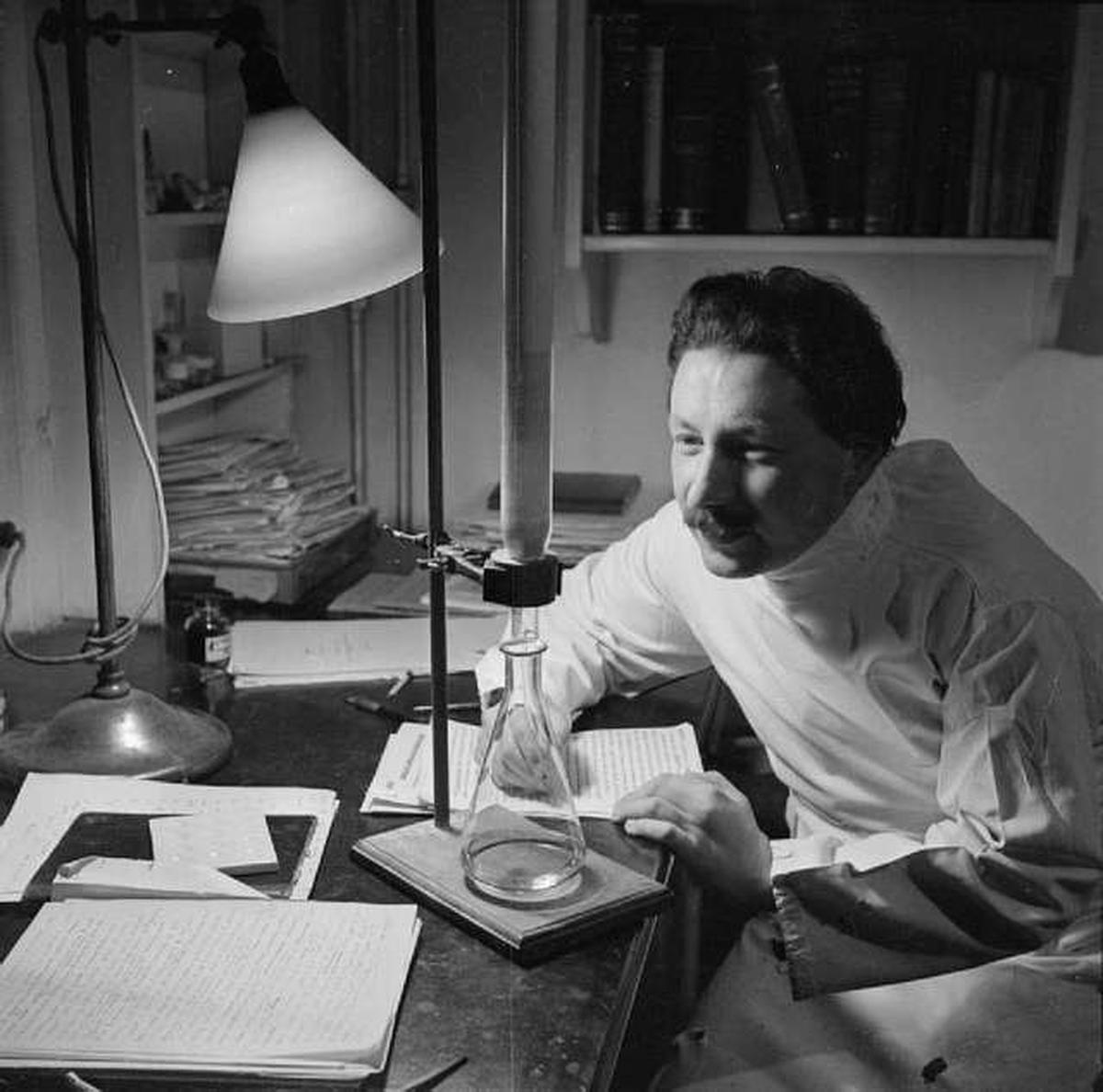

Ernest Chain undertakes an experiment in his office at the School of Pathology at Oxford University.

| Photo Credit:

Imperial War Museums

The duo began their work on penicillin in 1939 after Chain had come across Fleming’s paper on the antibacterial qualities of penicillin. While confirming Fleming’s findings were one thing, taking it a step further and purifying penicillin was another thing altogether. English biologist and biochemist Norman Heatley was a crucial member of the team in this regard.

Heatley had the vision to devise a method that could be successfully employed to extract and purify penicillin. Cultures of mould grown in hundreds of vessels in the Dunn School labs served as the starting point. The fact that he came up with an automated process using bedpans, milk churns and baths all put together might not sound like much, but it definitely worked.

First real test

At the height of World War II, Florey’s team was at a point where they could conduct an important experiment. The plan was to test penicillin on mice – the first real test to find out if it could function as an antibacterial drug.

On May 25, 1940, eight mice were infected with streptococci bacteria using lethal doses. Four of these mice were then administered penicillin, even as the remaining four did not receive it. While the four mice that didn’t receive penicillin were dead in the morning, those that had received it survived for anywhere between days to weeks.

Even though the results were abundantly clear and in favour of them, the task of treating humans – roughly 3,000 times bigger than mice – was still some time away. For starters, they set about producing more penicillin, so much so that the Dunn School literally turned into a penicillin factory.

Human trials

By February the following year, Florey believed they had enough to begin human trials. He enlisted Charles Fletcher, a young doctor at the Radcliffe Infirmary at Oxford, to help him with the new task at hand. On February 12, 1941, Albert Alexander became the first patient to be treated with penicillin.

While the cause of Alexander’s infections weren’t revealed in his hospital notes, it is clear that he was shifted to the Radcliffe Infirmary once his infection had become severe. Alexander received penicillin injections from Fletcher regularly over four days. Despite significant improvement within the first 24 hours, there wasn’t enough penicillin to continue the treatment, notwithstanding the team’s best efforts. As they ran out of supply even before the cure was complete, Alexander relapsed early in March and died a month later.

Even though some early patients did pass away, a number of them who were seriously ill did make recoveries. With people making full recoveries from infections that had previously been killing others, the claim that penicillin was a magic drug did seem to ring true.

In the years that followed, companies in the U.S. and the U.K. chipped in and penicillin was mass produced. The ongoing war meant that there was no dearth for demand and the drug in fact had to still be rationed to give the “best military advantage,” according to the U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill.

Broad-spectrum antibiotic

A broad-spectrum antibiotic that is used to treat various bacterial infections, more than 1 million people were treated with the drug by 1945, as opposed to less than 1,000 early in 1943. In the decades that followed, penicillin has been used to treat a wide variety of bacterial infections. Some bacteria, in fact, have even developed resistance to penicillin by now, making it less effective in some cases. Nevertheless, penicillin – the discovery of which ushered in the modern age of antibiotics – continues to be a potent antibiotic and is also used in combination with other drugs.

Most people might associate penicillin only with Fleming, even though he failed to realise its true potential. Certain others would know about the contributions of Florey, Chain, Heatley, and Fletcher and how they made penicillin the wonder drug that it is. Fewer still might be aware that the 1945 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine was shared by Fleming, Florey, and Chain “for the discovery of penicillin and its curative effect in various infectious diseases.” Spare a thought, however, for those eight dead mice.

Published – May 25, 2025 01:05 am IST