Life as a Dream

Born on March 14, 1854 at Strehlen, Germany (now Strzelin, Poland), Paul Ehrlich was the son of Ismar Ehrlich and his wife Rosa Weigert. Educated at the gymnasium at Breslau, he went on to study at the Universities of Breslau, Strassburg, Freiburg-im-Breisgau and Leipzig. With a dissertation on the theory and practice of staining animals, Ehrlich obtained his doctorate of medicine by 1878.

Ehrlich showed flashes of what was to come even when he was at school. When, as a schoolboy, a teacher assigned an essay on the topic “Life as a Dream,” he chose to take a less trodden path.

When presented with such a topic, it is easy to wax philosophical, which was exactly what most of his classmates did. Ehrlich, however, had other ideas. He presented his thoughts about the dependence of life on normal oxidation processes, with nerve activity as the primary example. He theorised further that dreams were a form of oxidation resulting in the phosphorescence of the brain, thus connecting it to the topic given by his teacher.

Wins the Nobel Prize

Ehrlich’s research career took him from dyes to immunological studies, the field with which his name is now forever associated. German physician and microbiologist Robert Koch, considered one of the founders of modern bacteriology, invited Ehrlich to be one of his assistants when appointed the director of the newly established Institute for Infectious Diseases in Berlin in 1890.

Among his colleagues here were Emil von Behring and Shibasaburo Kitasato, bacteriologists who co-discovered antitoxins for diphtheria and tetanus. Even as they developed their serum therapy in the final decade of the 19th Century, Ehrlich pitched in by improving and mass-producing high-quality diphtheria antitoxin for human use.

Ehrlich’s work didn’t go unnoticed and when the Institute for Serum Research and Serum Testing (now Paul-Ehrlich-Institut) was set up in 1896, he was appointed as its director. He did further work on immunology here.

Ehrlich shared the 1908 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine with Russian-born zoologist and microbiologist Elie Metchnikoff “in recognition of their work on immunity.” Both Ehrlich and Metchnikoff had their own separate ways of understanding the immune responses, both of which are now deemed necessary to our understanding of the immune system. While Metchnikoff studied the role of white blood corpuscles in destroying bacteria, Ehrlich provided a chemical theory. Using this theory, he explained the formation of antitoxins, or antibodies, to fight the toxins that were released by bacteria.

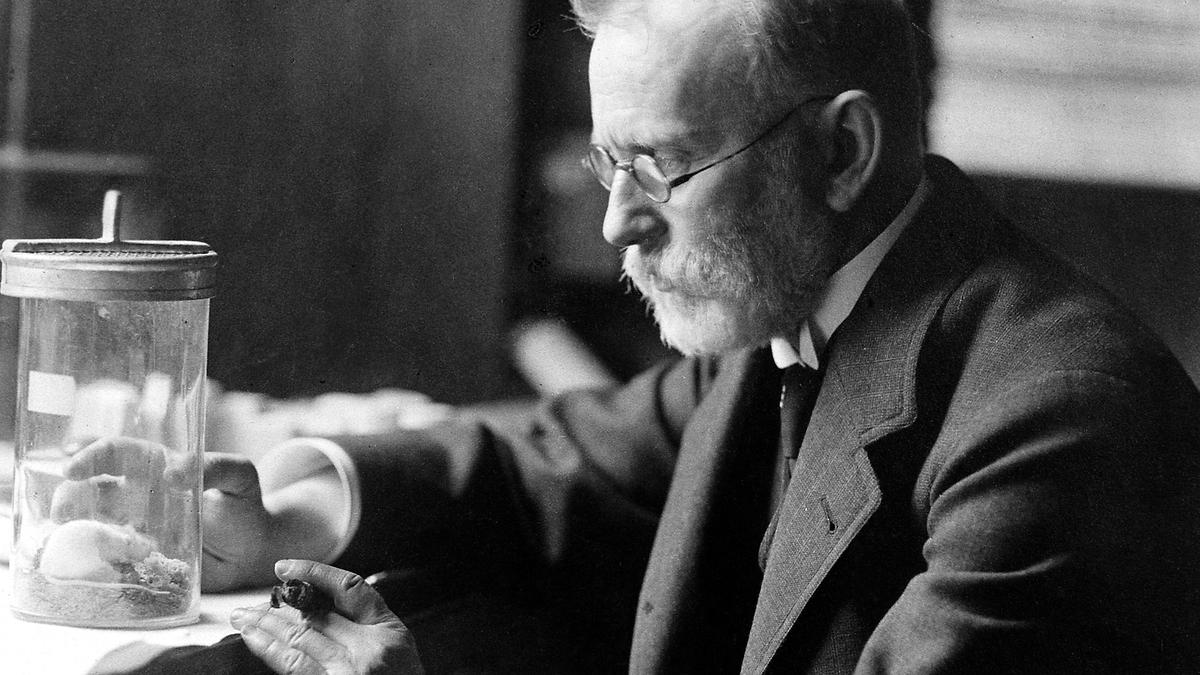

Portrait of Paul Ehrlich and Sahachiro Hata

| Photo Credit:

Wellcome Library, London. Wellcome Images / Wikimedia Commons

Coins the term “chemotherapy”

Ehrlich saw serum therapy as an ideal way of contending with infectious diseases. Where effective sera could not be discovered, Ehrlich decided to turn to synthesising new chemicals. This was in line with his own belief that chemicals could kill infectious microbes without affecting their human hosts. It was in this regard that Ehrlich coined the term chemotherapy, even though it has now come to refer to a type of cancer treatment.

Just as antitoxins go to the toxins to which they are specially related, Ehrlich aimed at finding substances which have specific affinities for pathogenic organisms. These “magic bullets,” as Ehrlich expressed it, will go straight to the organisms at which they were aimed, acting only on them without affecting the hosts.

These ideas were best summed up by Ehrlich himself when he once spoke about these drugs: “We must search for magic bullets. We must strike the parasites, and the parasites only, if possible, and to do this, we must learn to aim with chemical substances!”

Salvation through Salvarsan, Neosalvarsan

Along with an organic chemist, Alfred Bertheim, Ehrlich was responsible for determining the correct structural formula of atoxyl. This came at a time when the spirochaete that causes syphilis was discovered.

While atoxyl, an arsenic compound, was known to be effective against certain spirochaetes, it was too toxic for use in humans. Ehrlich sought a drug that would work specifically against the spirochaete that causes syphilis and used atoxyl as a starting compound to synthesise others.

With access to funds and an army of assistants at his disposal, Ehrlich set about churning out drugs that were tested and stored in a systematic manner. Among these were arsphenamine or compound 606, which was set aside in 1907 as being ineffective.

Ehrlich’s former colleague Kitaso sent one of his pupil, Sahachiro Hata, to work at Ehrlich’s institute. Having learnt that Hata had succeeded in infecting rabbits with syphilis, Ehrlich instructed one of his latest assistants to test the drugs they had created.

On August 31, 1909, Hata injected compound 606 to one such rabbit – now the first ever session of chemotherapy, so as to say. To his astonishment, the rabbit improved and in three weeks time its syphilitic ulcers were completely gone.

The move from rabbits to human beings was gradual, but it was met with success all the way. Ehrlich manufactured and announced compound 606 under the name Salvarsan and it was extraordinarily effective, especially if administered during the early stages of the disease. In short, Salvarsan was the first of Ehrlich’s first magic bullets.

Salvarsan treatment kit for syphilis.

| Photo Credit:

Science Museum, London. Wellcome Images / Wikimedia Commons

Even though harmful side effects remained nominal, it didn’t stop some from attacking Ehrlich. Undeterred, Ehrlich continued to supervise chemical modifications. One of these, compound 914 to which the name Neosalvarsan was given, turned out to be another effective drug. Even though Neosalvarsan was less curative than Salvarsan, the fact that it could be more easily manufactured, more soluble, and more easily administered meant that it had a role to play.

Despite the initial opposition faced, both Salvarsan and Neosalvarsan turned out to be accepted treatments for human syphilis. They remained the most effective drugs against syphilis until the 1940s, when antibiotics made their way.

Ehrlich was distressed by World War I and had a slight stroke during Christmas in 1914. His health started to decline after that and he succumbed to a second stroke in August 1915. The London Times, in its obituary, acknowledged Ehrlich’s contributions by mentioning that “The whole world is in his debt.” We certainly are.

Published – August 31, 2025 12:19 am IST