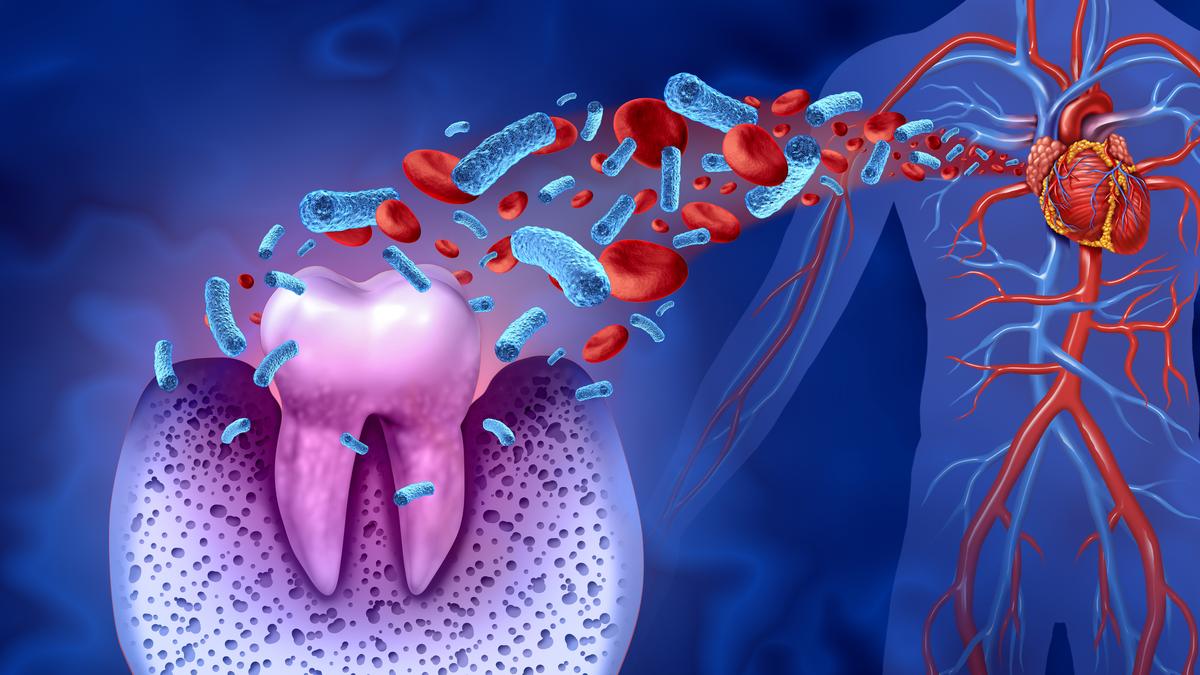

A new study published in the Journal of the American Heart Association has found that viridans streptococci, a group of common oral bacteria, can form sticky bacterial layers called biofilms deep inside atherosclerotic plaques, remaining hidden from the immune system until the moment of rupture. The findings suggest that oral bacteria could persist in coronary arteries and contribute directly to fatal heart attacks.

Coronary artery disease has long been understood as a condition driven by cholesterol deposition, high blood pressure, diabetes, and smoking, all of which promote chronic inflammation in the arteries. Alongside these established factors, researchers have also proposed infection-related inflammation as a trigger for plaque rupture, leading to heart attacks. Previous studies had linked microbes related to pneumonia, herpes viruses, and ulcers inside atherosclerotic plaques, although none had been linked directly to rupture events.

“This study is a step forward in our understanding of the reasons for increased incidence of heart attacks in individuals with gum disease and the increased prevalence of gum disease in patients with heart attacks,” C.C. Kartha, ex-professor of eminence at the Rajiv Gandhi Centre for Biotechnology, Thiruvananthapuram, said.

Plaques and heart attacks

The new study, by a research team at Tampere University in Finland, examined coronary arteries from 121 sudden-death autopsies and 96 patients undergoing vascular surgery. Using DNA detection tests and microscopic staining, the researchers found bacterial DNA in a significant proportion of samples. Viridans streptococci were the most frequent species, present in about 42% of both autopsy and surgical cases.

The bacteria were seen forming biofilms within the lipid-rich cores of plaques, where immune cells called macrophages largely failed to notice them, suggesting they could persist silently for years. In ruptured plaques, however, the bacteria had shifted location into the outer layer that covers the plaque and prevents it from spilling into the bloodstream. Here, they were associated with the activation of toll-like receptor 2 (TLR2), an immune sensor that helps the body detect microbes. This pattern was consistent with inflammation leading up to rupture.

The team also took steps to rule laboratory contamination out. Lead author Pekka J. Karhunen explained that their controls showed no signal when unrelated bacteria were tested and that the same bacterial signatures were found in both autopsy and surgical cases.

The question now is whether these hidden bacteria can be treated. Attempts to treat coronary disease with antibiotics have repeatedly failed in large clinical trials, and the Finnish group suggested that biofilms may explain why. The bacteria embedded in these structures strongly resist both antibiotics and immune clearance.

Prof. Soma Guhathakurta, cardio-vascular and thoracic surgeon, and Honorary Advisor at Namar Heart Hospital, Chennai, said the oral bioburden could one day be measured in suspected high-risk individuals, who could be offered preventive penicillin treatment in a strategy modelled on the way doctors manage rheumatic fever. While this is speculative, such proposals show how the findings are already opening new lines of inquiry.

Oral health and heart risk

Dentists have long observed how bacteria in dental plaque can alternate between stable biofilms and free-floating, invasive forms. “Bacteria in dental biofilms can form robust communities that, under certain conditions, can disperse and release more virulent cells,” Delhi-based orthodontists Hiten and Priyanka Kaushal Kalra explained.

They said that such shifts are plausible in arteries as well as through microtears in the blood vessel lining, on prosthetic surfaces such as valves or stents, and the lipid-rich environment of plaques. When conditions change, dispersed free-floating cells can re-emerge and penetrate deeper tissues, like those seen in infective endocarditis, a serious infection of heart valves.

The Kalras pointed to population-level evidence linking oral care with cardiovascular health. “The ARIC study showed regular dental care was associated with a 23% lower stroke risk, while a large Korean cohort found more frequent tooth brushing linked to reduced cardiovascular events.” Untreated periodontal disease, apical periodontitis and chronic dental infections, by contrast, correlate with higher risks of stroke and coronary disease.

They emphasised early management of gum disease, prompt treatment of abscesses or necrotic teeth, and regular cleaning, alongside collaboration between dentists and cardiologists in high-risk patients.

Public health resonance

The insights from dentistry highlight the everyday routes by which bacteria could reach the arteries — a concern made sharper in India’s context. Cardiovascular disease affects people in India of younger ages even while untreated oral disease remains widespread.

“The oral-cardiac link is well known, though the causal link has not been established,” said Dr. Kartha. “It is important to educate the public regarding the mouth–heart connection and the importance of oral hygiene as well as detecting and treating gum disease early, especially in patients with risk factors such as high LDL and diabetes.”

Prof. Guhathakurta added that oral swab surveillance after the age of 40 could be one way to test the biofilm-heart link in community settings, if validated by further research.

The Finnish group is also extending its investigations. “We aim to publish our bacterial genetic sequencing findings on the whole microbiome of coronary atheromas in the near future,” said Dr. Karhunen. Looking further ahead, he added, “We also aim to study the possibility of developing a vaccine against bacterial biofilm formation and bacterial-induced clotting.”

These ideas reflect a broader effort to move beyond association and determine whether targeting hidden biofilms can alter the course of coronary disease.

For now, cardiology practice remains centred on cholesterol control, blood pressure management, and diabetes care. Yet the new findings and the voices of clinicians and dentists alike underline that oral health may be more closely tied to heart health than is recognised. Whether through everyday gum care or future biofilm-targeting therapies, the bacteria in our mouths could prove to be an overlooked player in the story of India’s most common killer.

Anirban Mukhopadhyay is a geneticist by training and science communicator from New Delhi.

Published – October 07, 2025 08:30 am IST