Much has been written about the universally loved Jane Goodall, primatologist and animal rights campaigner, on whom awards and honours far too numerous to list have been showered. She passed away on October 1 aged 91. One recognition, however, she did not but should have received is the Nobel Peace Prize. For all her life, Goodall worked for peace and harmony not just between humans but between Homo sapiens and all life on Earth.

Her own words best describe the start of her seven-decade-long journey to convince humanity to protect our magical planet: ‘If you are interested in animals,’ someone said to me about a month after my arrival in Africa, ‘then you should meet Dr. Leakey.’ I had already started on a somewhat dreary office job, since I had not wanted to overstay my welcome at my friend’s farm. I went to see Louis Leakey at what is now the National Museum of natural history in Nairobi, where at that same time he was Curator. Somehow he must have sensed that my interest in animals was not just a passing phase, but was rooted deep, for on the spot he gave me a job as an assistant secretary.

First encounter

I never got to meet Jane Goodall but she entered my life in 1966, six years after she began her work with the legendary Louis Leaky in Tanzania’s Gombe Stream National Park, when the National Geographic magazine placed her on their cover. Down the years, I could not help but compare her to the other Jane… Tarzan’s Jane, about whom she recently said with an impish smile: “Tarzan married the wrong Jane.” Her fascination for Africa and chimpanzees was undoubtedly influenced by her love for Tarzan of the Apes (1912) and Tarzan’s sidekick Cheeta the chimpanzee. Her version was a stuffed toy chimp named Mr. H. “[He] goes everywhere with me. We’ve been to 59 countries together and he’s probably been touched by about nearly 4 million people,” she once said.

British anthropologist and primatologist Jane Goodall in September 1974.

In 1978, I bought a large format pictorial book, Savage Africa, authored by Hugo van Lawick, only to discover that Jane Goodall was Lawick’s former wife, and that they had jointly put together a book in 1971, Innocent Killers, with Goodall doing the writing and Hugo the photography. The detailed descriptions of hunts by carnivores such as hyenas, cheetahs and leopards were graphic and gory, but they conveyed an elemental truth: unlike humans, wild animals were not ‘cruel’ as judged by ethical human standards. Animals ate what they killed. Nothing went to waste.

Blazing a trail

Down the decades, Goodall showed the world that it was possible to love animals (she likes dogs more than chimps!). She told us that chimps lived in societies akin to ours and used tools to access food, an ability thus far attributed only to humans. What’s more, they had distinct personalities. Some, like one individual she named David Greybeard, displayed likeable traits, while some were unlikeable, even cannibalistic. None of these field observations came easy. It took years to win the trust of the chimps, never hiding from them until she became a part of the non-threatening backdrop, a harmless pale-coloured ape. No naturalist had ever attempted this before. The most important of all her observations was the ability of apes to insert twigs into termite nests, pull them out repeatedly with ants attached and consume as food. When Louis Leaky saw evidence of this from images shot by a National Geographic photographer, he sent this now-famous telegram to his protégé: “NOW WE MUST REDEFINE TOOL STOP REDEFINE MAN STOP OR ACCEPT CHIMPANZEES AS HUMAN”.

Goodall faced considerable opposition over the years, largely by testosterone-driven males who questioned both her capability and ability to survive in the rough-and-tumble world of Africa’s jungle life. Her mother, nevertheless, travelled all the way to be with her young daughter as the attitude of men spurred her on to achieve more and discover more, and cut a trail not merely in Africa but clean through academia in England.

Misplaced criticism

She was also the target of misplaced criticism from human rights activists who accused her of protecting apes at the cost of local human communities. Working in a male-dominated sector in her early days, she was unfairly criticised for being an amateur with anthropomorphic biases that ended up superimposing human attributes and capabilities onto wild apes.

A decade ago, some academics pointed out that a manuscript of hers, for Seeds of Hope (2013), omitted crediting sources. Emily Brelage of DePauw University wrote, “It’s important to not ignore the flaws that make them [admired heroes] human, while we celebrate what makes them great.” With characteristic grace, Goodall responded that she would delay publication with added credits, saying, “I hope it is obvious that my only objective was to learn as much as I could so that I could provide straightforward factual information.”

Scientist Jane Goodall studies the behaviour of a chimpanzee during her research in February 1987 in Tanzania.

She never needed to respond to the accusations of anthropomorphic biases because in 1965, Newnham College in Cambridge University settled the issue by accepting her deeply scientific doctoral thesis titled ‘The Behaviour of Free-living Chimpanzees in the Gombe Stream Reserve’. Valerie Jane Morris Goodall was now Dr. Jane Goodall.

To the human rights activists, she responded as saying that protecting the apes’ jungles was in the interests of the African people whose jungles were being brutally colonised by the industrial North.

Even today, the developed world continues to trot out arguments to justify deforestation, a primary cause of our current climate crisis. In my book, that amounts to intergenerational colonisation. In her last days, Goodall travelled the globe, met young and old, villagers, royalty and power brokers, urging them all to rein in carbon, protect the biosphere, and leave our children a climate-safe world.

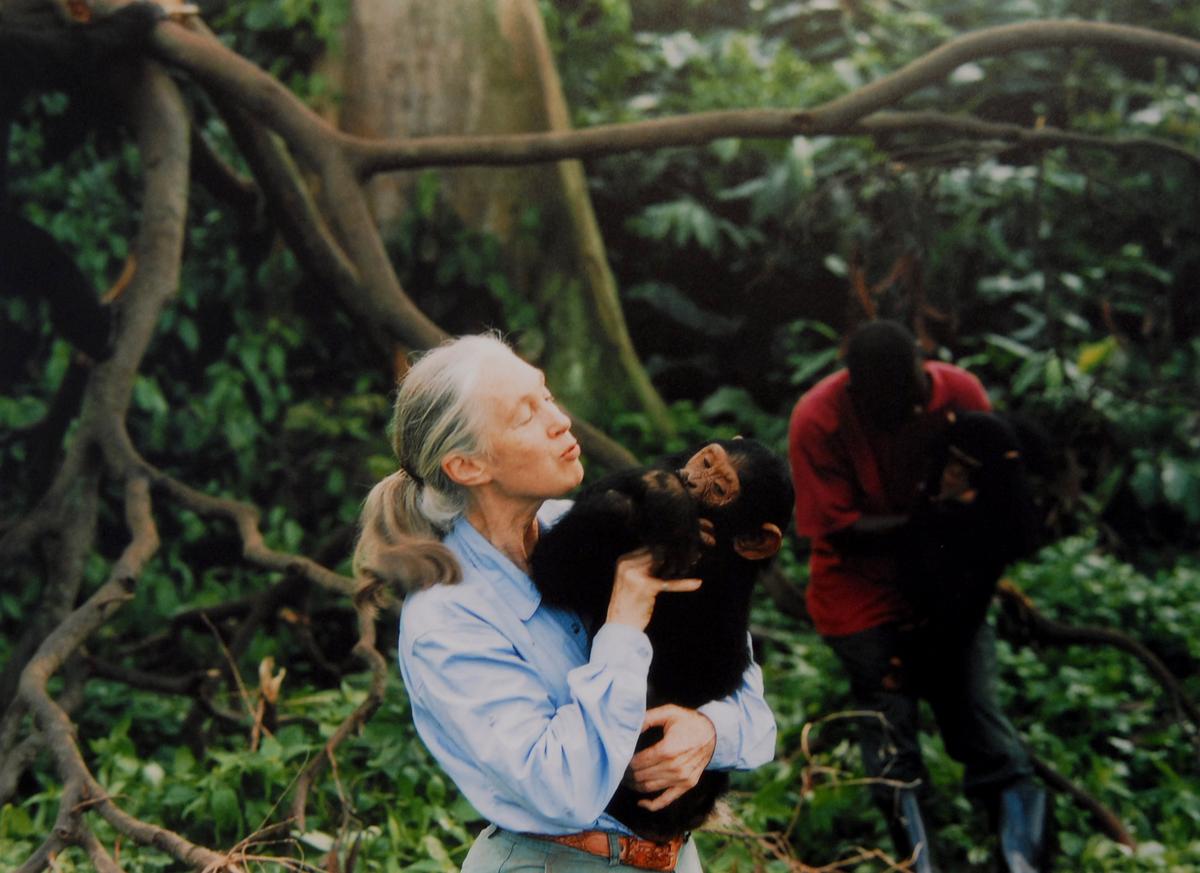

Jane Goodall, English primatologist, ethologist, and anthropologist, with a chimpanzee in her arms, in 1995.

She was met everywhere with what can only be called veneration. Jane Goodall did her job on Planet Earth by re-emphasising conclusively what Charles Darwin had posited on November 24, 1859, the day his controversial book On the Origin of Species was published. He said we were descended from apes. She revealed that chimps’ brains were capable of using tools, a fact that scientists of the day refused to accept.

Both suffered severe criticism from religious quarters that believed only humans had souls, and were given dominion over all other life by ‘the creator’. What is more, Jane Goodall sprinkled us with the magic of hope with the example of a life well lived.

The writer is editor of Sanctuary Asia and founder of Sanctuary Nature Foundation.

Published – October 09, 2025 06:16 pm IST