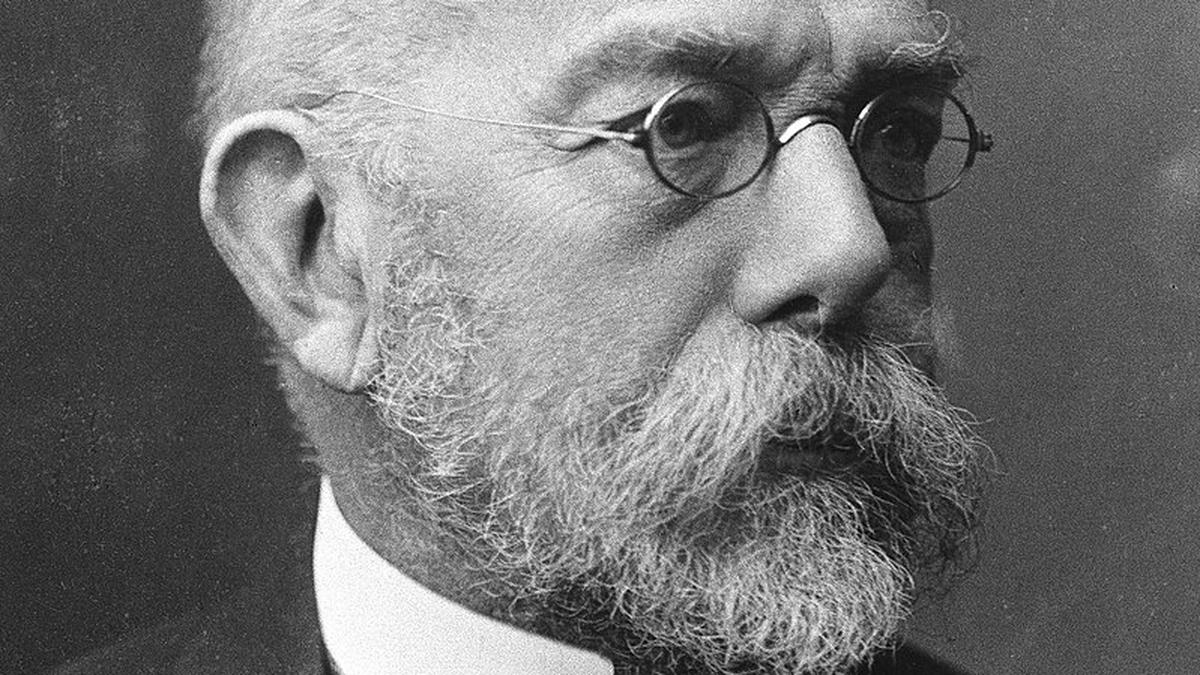

In 1905, German physician and microbiologist Robert Koch was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine “for his investigations and discoveries in relation to tuberculosis.” At a time when TB claimed millions of lives, Koch’s identification of Mycobacterium tuberculosis as the causative agent transformed medical science and confirmed that the disease was infectious, not hereditary. The discovery not only guided prevention and treatment but also shaped public health strategies worldwide.

Early years and scientific beginnings

Robert Koch was born on December 11, 1843, in Clausthal, a mining town in the Harz Mountains of Germany. A precocious child, he taught himself to read by age five and later studied medicine at the University of Göttingen, where pathologist Jacob Henle, an early proponent of germ theory left a lasting influence.

After graduating in 1866, Koch worked as a country doctor and briefly served as a military physician during the Franco-Prussian War. Without access to formal laboratory facilities, he built his own microscopes and equipment, devising simple but effective methods that foreshadowed his breakthroughs in microbiology.

Koch’s first great success came in 1876, when he identified Bacillus anthracis as the cause of anthrax. He introduced new methods to culture bacteria in pure form using gelatin and later agar, and developed staining techniques to make microbes visible under the microscope.

From these experiments, he formulated Koch’s postulates, four criteria to establish a causal link between a microorganism and a disease. These postulates provided microbiology with its first rigorous framework, which continues to influence infectious disease research today, though adapted for viruses and molecular methods.

Work on tuberculosis

Koch’s most celebrated discovery came in 1882. In a landmark lecture to the Berlin Physiological Society, he announced that he had identified the tubercle bacillus (Mycobacterium tuberculosis) as the cause of tuberculosis. By applying his staining techniques, he demonstrated the rod-shaped bacteria in diseased tissues, proving that TB was infectious.

This revelation overturned the long-held belief that tuberculosis was hereditary, ushering in public health interventions such as isolation of patients, improved ventilation, sanitation reforms and pasteurisation of milk. A century later, the World Health Organization designated March 24 — the date of Koch’s announcement as World Tuberculosis Day, which is now marked globally to raise awareness and renew commitments to TB control.

Global influence

Koch’s influence extended to many other diseases. In 1883, during an epidemic in Egypt and later in India, he identified Vibrio cholerae as the causative agent of cholera, proving its link to contaminated water. His expeditions to Africa broadened the field of tropical medicine, where he studied rinderpest — a highly contagious and often fatal viral disease of cloven-hoofed animals, particularly cattle and buffalo, known as cattle plague; malaria and sleeping sickness.

In 1891, Koch founded the Royal Prussian Institute for Infectious Diseases in Berlin, later renamed the Robert Koch Institute, which remains Germany’s national public health authority and a leading global centre for disease surveillance and epidemic response. His laboratory also became a training ground for young microbiologists from across the world, spreading bacteriological methods internationally.

Controversies and challenges

Not all of Koch’s contributions were without dispute. In 1890, he introduced “tuberculin” as a potential cure for TB, which initially generated enormous public excitement but was later shown to be ineffective and sometimes harmful. Despite the disappointment, tuberculin became an important diagnostic tool, the tuberculin skin test, still in use today.

Koch also argued that bovine tuberculosis rarely infected humans, a stance later proven wrong, especially concerning the transmission through contaminated milk.

Legacy and impact

Koch’s Nobel Prize recognised his landmark work on tuberculosis, but his impact reached far beyond a single disease. Alongside Louis Pasteur, he is regarded as a founder of modern bacteriology. His postulates, staining techniques, and culture methods shaped experimental standards that continue to guide how new pathogens are studied.

The World Health Organization and national public health agencies still build on Koch’s foundations in TB control and epidemiology. Programmes such as directly observed treatment (DOTS) and molecular diagnostic approaches trace their lineage back to his discovery of the tubercle bacillus. The Robert Koch Institute continues to carry forward his mission, playing a leading role in infectious disease research and pandemic response.

Robert Koch died on May 27, 1910, at the age of 66. His discoveries remain embedded in both science and public health. His Nobel-winning research is commemorated every year on World Tuberculosis Day, and his name endures in global institutions, reminding us that rigorous science can transform human health and society.

Published – September 14, 2025 02:35 pm IST